Tribal art, from the beginning to the 21st century

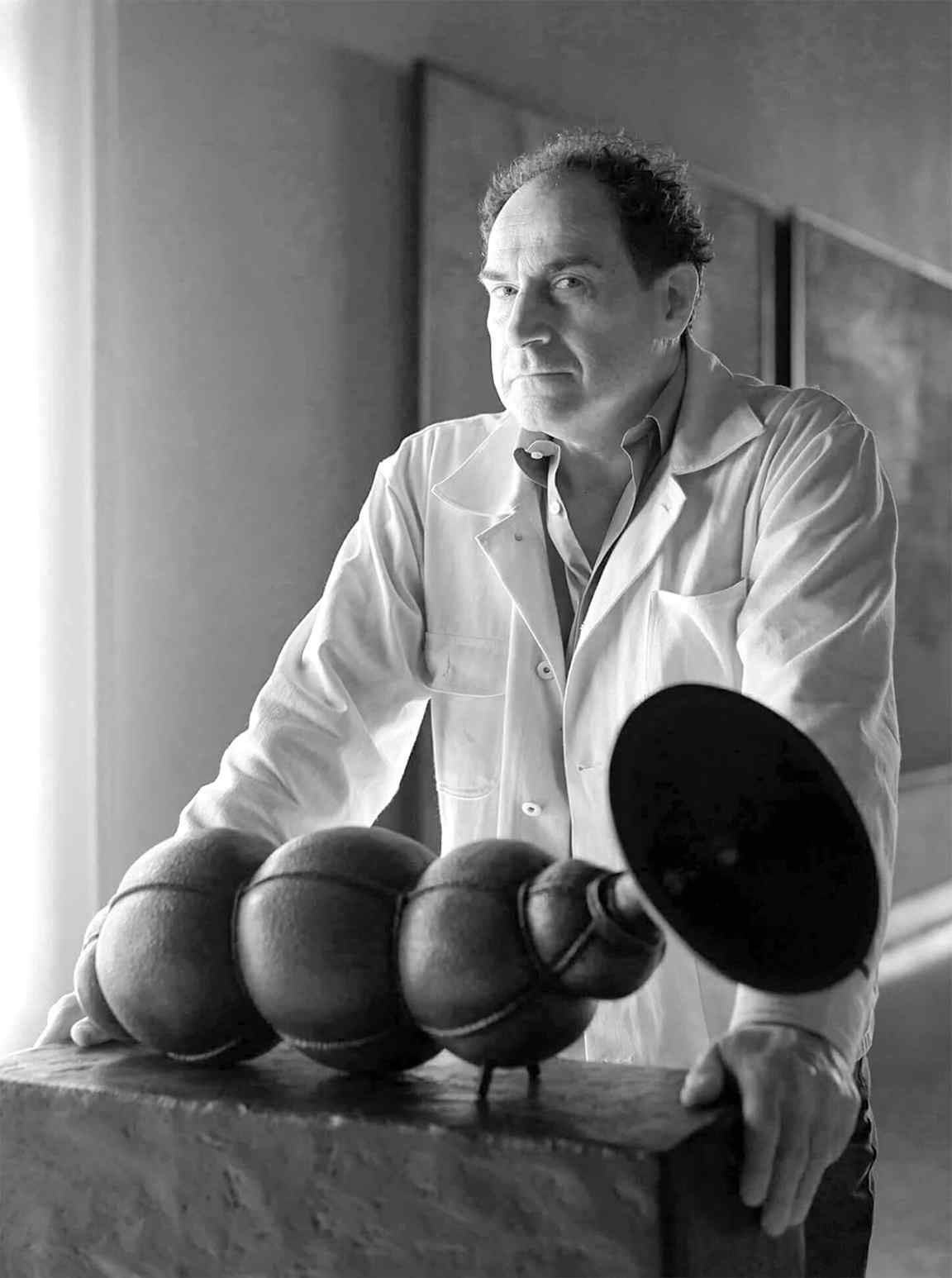

From the 26 May to the 27 August, Carpenters Workshop Gallery and Bernard Dulon gallery are creating a dialogue between design and tribal art in a much anticipated exhibition.

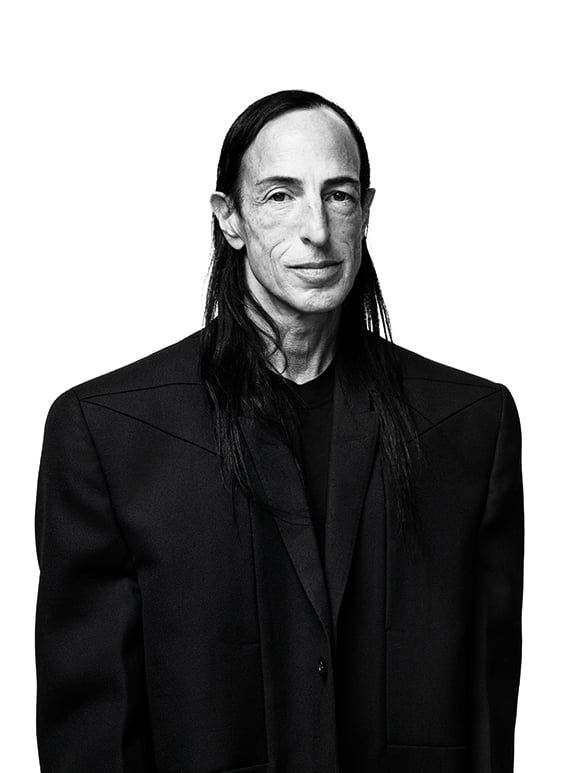

Since its creation ten years ago, Carpenters Workshop Gallery has unconsciously developed an aesthetic and creative line that is evident in many of its creative endeavors. An imaginary link is clear in the work of Ingrid Donat who draws from her Creole roots, and it is equally seen in the work of Rick Owens, Wendell Castle, Kendell Geers and Atelier Van Lieshout.

Come and discover this ancestral link in a confrontation of major Tribal artworks selected by one of the most important galleries in the world in this sector: Galerie Bernard Dulon. Today, it brings a singular perspective on two disciplines that appear at first as if they are opposites.

‘Tribal’ aims to break down the traditional approach that we usually think of when art poses the question, “Without forgetting, can we pass beyond the borders of genres, eras, continents and cultures?”

Ancient Comparisons

Tribal art, particularly from Africa, has always generated a large interest from the decorative and contemporary art community. At the beginning of the 20th century, artists began to collect sculptures originating from Africa. Therefore,

the attraction to African objects is nothing new.

Contact between Europe and Africa began after indigenous artifacts were taken as souvenirs from trips to the continent and introduced into European collections as exotic curiosities in the 15th century. Yet, a movement born in Paris lingered with insistence on the inspiration taken from sculptures (masks and statues). This enthusiasm quickly won over Europe and soon the rest of the world caught on in the 1920s.

“Primitivism” expressed a refusal of bourgeois values represented by the industrialization that galloped through and devastated social and cultural areas. A number of artists turned towards the so-called “primitive” societies of Africa and Oceania. They were attracted by their way of life, inspired by their closeness to nature, and by their indigenous artwork. They were drawn by these formal conceptions to interpret their own sensibilities.

These artists also saw the equal attraction of authenticity and spontaneity– two values that they felt were pushed aside by the fashionable life of bourgeois materialism that became more and more important in the 19th century. The artists were familiarized with “primitive art” found in ethnographic museums and related dealers. Face-to-face with western public perception, African artifacts passed progressively from the sphere of ethnographic objects to those of artistic works. The precursor to this artistic approach come from the likes of Paul Gauguin.

Picasso also expressed an interest in African art from 1907. Other European artists from Germany to Czechoslovakia soon followed suit as interest in Tribal Art began to provoke their inspiration as they searched for aesthetic ideals. This

trend soon grew internationally and took many forms as it followed the desires of artists contemporary to the 20th century. In the decorative arts domaine, Pierre Legrain is one example of an artist who took inspiration from African

furniture. He created a number of seats, notably curule stools, inspired by objects taken from French colonies in Africa such as Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Dahomey, and Gabon that were exhibited multiples times in Paris.

In 1919, an exhibition took place called “Negro Art and Oceanic Art”, and in 1923, another named “Indigenous Art of the French Colonies” was held at the Marsan pavilion at the Louvre. These two exhibitions were thanks to clients and patrons of Pierre Legrain, Jacques Doucet and Jeanne Tachard who participated by loaning their private collections of African art.

The mask is very present in this exhibition, a universal symbol that embodies the incarnate bridge between cultures and disciplines. Traditionally the use of masks is present in a diverse variety of activities found in everyday village life: the representation of ideal feminine or masculine beauty, the changing of the seasons, the power of a chief or king, magic, or even the initiation of young men into secret societies. African artists are usually anonymous; they do not sign their works of art.

The creation of masks, as seen here, responds to the demands of use, effectiveness, and the knowledge of its creator. A dialogue as much as a confrontation, the masks of the Bekom and Fang people in the 19th century respond to the mask-sculptures of South African artist Kendell Geers and British artist Thomas Houseago.

Inspired both by cubism and African masks, the contemporary artists claim here to be creating figurative works. Just like others before him such as Picasso, Houseago is clearly fascinated by the tribal art of Africa and Oceania.

Beyond masks, the exhibition aims to create structural relationships or discussion-confrontations. As seen in the “Curial” armchair made of fossilized wood, this work responds to the post-modern armchair ‘Leviathan’ by Kendel Geers which is made of bronze tires. This is an awe inspiring clash between the story of thousand-year old African art and the critique of its of modern interpretation. The armchair ‘Onedent,’ composed of bone, by Rick Owens evokes the animal world which is considerably present in Tribal Art as also demonstrated in a horned mask from the Kwele people seen here.

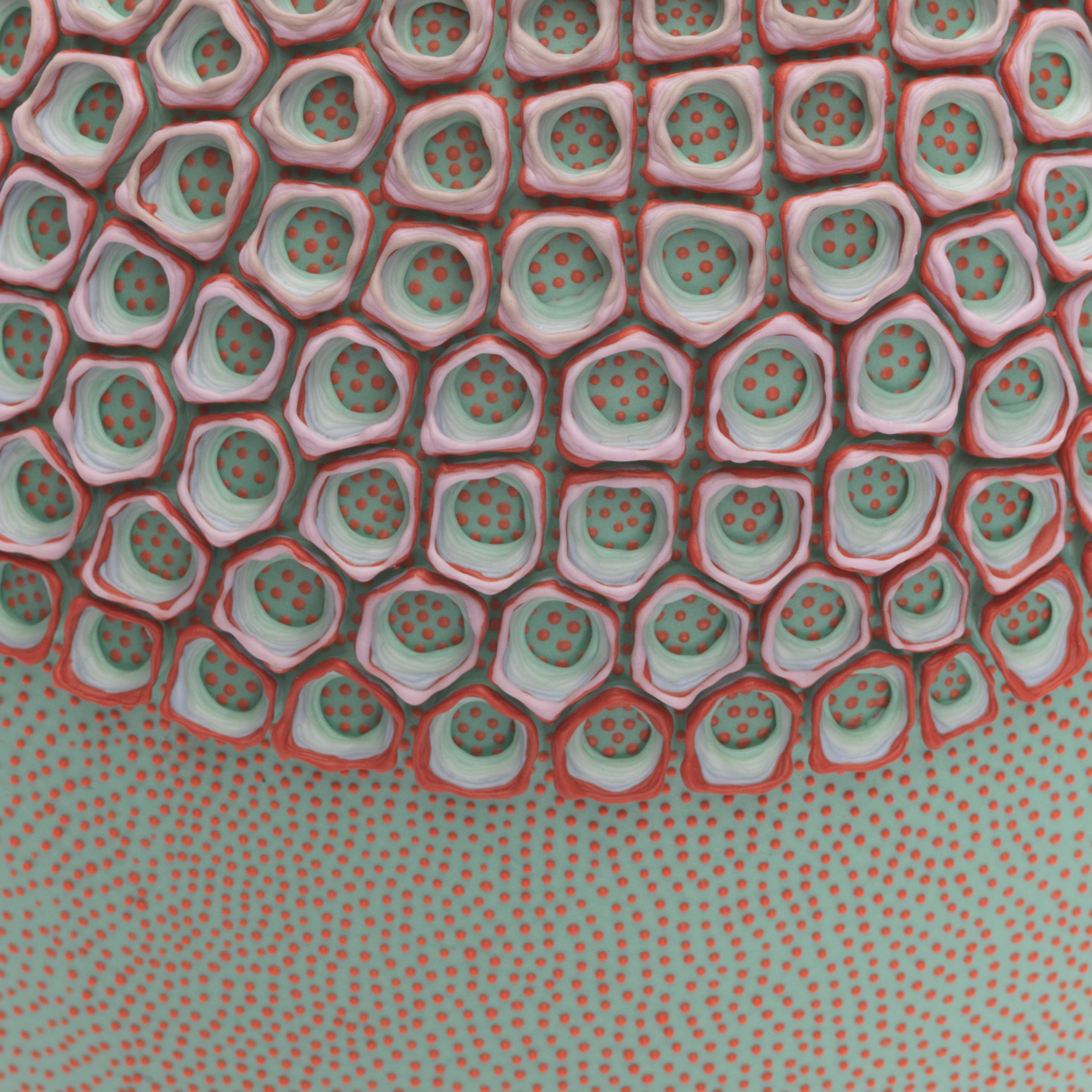

Joep Van Lieshout found inspiration in the Western fantasy of cannibalism in tribal societies as seen in ‘Gastronomy,’ a low table made of bronze with black patina; it depicts a scene of anthropophagy. His ‘Sensory Deprivation Skull,’ a cranium styled armchair, evokes a fantastical western vision of African and Oceanic societies (as seen on the cover of the press kit). The ‘Cocoon’ table from Nacho Carbonell, shown in earthy colors, evokes the giant termite mounds of West Africa and Australia.

The pieces from Ingrid Donat that feature tribal motifs are reminiscent of scarification, and they interact with the ornamental treatment of a 19th century studded stool from the Sanngo people of the Democratic Republic of Congo. In comparison, an ancestral statue from the Mumuyé people of the Adamawa Province in Nigeria observes with intrigue the bronze statuettes created by Kendell Geers.

For certain artists, works from Africa or Oceania are a framework, or a pretext, to create social commentary. Yet, for others, it is a simple influence of shapes that it is never without its symbolism.

This exhibition does not give a profound knowledge of these arts, but these artists ask the question of the identity of their era as well as the encompassing influence of tribal art.

Tribal art is starting to be comprehended under a different status since its first contact with the west: from curiosities to colonial trophies followed by ethnographic objects and works of art. These artists take this question of supremacy towards the image of african objects and help transform it into a work of art.